Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) is not only common but has an enormous impact upon patients. Length of stay in hospital can be increased alongside increases in mortality (1). This effect on in-hospital mortality has attracted significant attention from the media in recent years (2). Increasingly, hospital blood reporting software includes AKI alerts based upon creatinine results in order to alert treating clinicians to AKIs earlier and aid detection.

Dr Aled Lewis is a Consultant Nephrologist at Glan Clwyd Hospital, North Wales. We talk about AKI from diagnosis through to management and some of the more complex acute complications that can accompany AKI and some special circumstances. This first part concerns diagnosis and general points. The second part will follow soon.

The Prolem With Acute Kidney Injury

Over recent years, AKI has received widespread media attention with news stories reporting excess deaths in UK hospitals (2). This has been accompanied by an increasing focus on early detection and prevention in hospitals and the community. One meta-analysis reported a pooled incidence of 21.6% for AKI in adults and an incidence of 20% for hospital-acquired AKI.

Whether a patient develops AKI prior to or during admission, both have the same impact on length of stay, increasing it potentially over twice that of a patient without AKI (3). Understandably, increasing severity of AKI also increases the length of stay. The risk of death is also increased. One UK based study found an Odds Ratio of 3.7 for those patients admitted with AKI and their risk of death overall (3). When investigated further, they revealed increasing risks with incresaing severity of AKI. The mortality associated with AKI has been estimated to be as high as 23.9% (1).

These patients who develop Acute Kidney Injury during their stay have an increased risk of readmission within the next 30 days compared with patients who do not develop AKI (4). These rates are not dissimilar to readmission rates for some chronic diseases but the important factor here is that AKI in the initial stage is not a chronic disease. Some, not all, cases are preventable.

In essence:

Assume all acutely unwell patients are at risk of Acute Kidney Injury

At Risk Patients

Any acutely unwell patient is at risk of Acute Kidney Injury. There are specific patient groups who are more at risk than others. Aled talks about a “double hit” when it comes to AKI. Initially, the patient might have some background reduction in their glomelular function that may not have been previously detected. The background to consider includes (5, 6):

- Age >65 years

- Chronic kidney disease, especially <60 ml/min/1.73m

- Heart failure

- Liver failure

- Diabetes

- Vascular disease

- Background nephrotoxic medication

- Neurological impairtment reducing access to fluids due to reliance on a carer for provision

These domains alone may result in a general reduction in glomelular function. The extra weight from an added insult may tip the kindeys over the edge from just about managing to detectable injury. The London AKI Network Manual groups posible insults by the mneumonic “STOP”:

- Sepsis & hypoperfusion

- Toxicity

- Obstruction

- Parenchymal kidney disease

These insults need to be appropriately managed in order to both prevent AKI, or when one has developed, treat the AKI itself. Without treating the underlying process that resulted in AKI, it is unlikely that the AKI will resolve. Alongside that, the modifiable risk factors that can be optimised need to be. Regrettably, we cannot reverse the aging process. We can ensure that liver and heart disease is appropriately managed, nephrotoxic medication is stopped and can improve glycaemic control for patients with diabetes.

Causes

The London AKI Network “STOP” mnemonic serves to remind us of the acute insults that cause AKI. Often, more than process is indicated and each patient must be considered individually. An alternative method to considering the causative processes would be grouping them as pre-renal, renal and post-renal:

Pre-renal

This is probably the most common cause encountered. Those most at risk from a pre-renal cause are those with an already low cardiac output and resultant low renal blood flow. These patients exist in a delicate balance and a “second hit” may tip the balance against them. That second hit would include anything that further reduces cardiac output and thus renal blood flow such as haemorrhage, vasodilating drugs, sepsis, dehydration (low fluid intake, vomiting, diarrhoea etc). One not to forget would be the patient with a process increasing intra-abdominal pressure or compressing renal arteries that reduces renal perfusion.

Renal

This group includes the rarer causes of the vasculidities and glomelularnephritis but also those that we may induce with our administered nephrotoxic medications resulting in interstitial nephritis. It also includes Acute Tubular Necrosis, which as a topic is huge in itself and results from renal ischaemia and even though it is an intrinsic process of the kidney actually results from a pre-renal cause (confusing isn’t it?).

Post-renal

The post-renal causes are anything that could cause an obstruction. These patients can become a distinct entity themselves when the obstruction is released and they enter a polyuric phase where AKI can worsen if output is not matched by input. The more commonly considered causes here would be prostatic enlargement causing a bladder outflow obstruction requiring catheterisation or a stone in the renal tract and resulting hydronephrosis.

Diagnosis

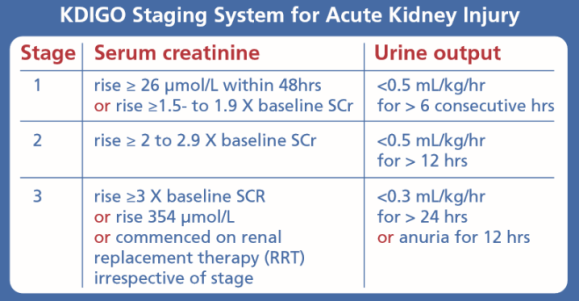

Diagnosis of AKI has becomes standardised by the KDIGO guidelines (7). They define AKI according to either changes in serum creatinine or level of urine output:

Most commonly, it is the creatinine criteria that will be used thanks to ease of measuring. It is very difficult to accurately record urine output per hour outside of a critical care or HDU setting. Where urine output monitoring is necessary, it is worth remembering that not all patient need a cetheter every time. If they are able to self void into a recepticle that allows for measuring then this will serve the same purpose and avoid unnecessary and invasive procedures.

Is the creatinine or eGFR a good measure of renal function? Perhaps not. This is because the rise in creatinine is delayed by potentially up to 72 hours following a reduction in filtration rate. In practice, this means what is seen biochemicaĺly can represent what happened to the patient 3 days ago. It is therefore worth paying attention to other changes such as urine output. Shifts in bicarbonate or potassium levels could be used as a cognitive stop point for us to consider whether acute changes represent alteration in kidney function if no alternative cause is present.

Investigations

Before considering any investigation remember:

AKI is a medical emergency and requires urgent attention

Acutely unwell patients need active and involved resuscitation to correct abnormal or unstable physiology

If you are concerned about the patient, escalate to your seniors or nephrology/critical care early

The obvious investigation to perform in any patient at risk of or felt likely to have an Acute Kidney Injury are U&Es. But what else do we order as well? Your local AKI bundle or pathway will likely have pre-specified investigations to perform but essential investigations include:

- U&Es – as well as the urea and creatinine, pay attention to the potassium and bicarbonate (if available) with shifts in these representing potential ocmplications of AKI

- Urine dipstick – a simple “UTI” should not cause AKI. Presence of a UTI and AKI suggests sepsis, rather than a simple UTI and needs managing appropriately. Presence of protein or blood or both raises questions about glomerlular disease.

- Venous/Arterial Blood Gas – initially, you may not have full renal function available, but an unexplained metabolic acidosis can hint towards a possible renal cause (see: Metabolic Acidosis) and will usually provide you with early electrolytes, particularly potassium, for which early action is important

- Lactate – will likely come as part of the blood gas or can be sent to the lab. Whilst a raised lactate is not diagnostic of sepsis, it should make you stop and think about the unwell patient in front of you if raised and encourage you to begin actively resuscitating the patient with fluids at least

- FBC – haemolysis, with anaemia and thrombocytopenia, is a potential cause of AKI but you may find a surprisingly high WCC which can start your investigations for infection as the driving insult

- Calcium/Bone profile – hypercalcaemia could point towards a cause either primarily or provide a hint towards possible myeloma. Hypocalcaemia is a potential complication of AKI and can lead to fatal arrhythmias

- USS/CT KUB – any patient with suspected obstruction should have an USS performed within 6 hours and urgent referral to urology if present. It may also show renal parenchymal damage or abnormalities that point towards a cause. Imaging should be performed within 24 hours for any AKI where the cause is not known or is not responding to appropriate therapy

Further investigations are going to be decided based upon the patient presentation and this list is not exhaustive:

- LFTs – liver failure is an important cause of AKI to seek out and manage. You may also find results consistent with biliary obstructions/infections that could be an underlying cause. Liver dysfunction may be another end organ damaged by an underlying process such as sepsis

- Urine Microscopy – in particular looking for red cell casts which would be suggestive of vasculitis.

- Vasculitis screen – some centres may mandate a vasculitis screen as standard work up for any Stage 3 AKI and any Stage 2 not responding to therapy. suspicion of vasculitis will be based upon history and examination.

- Myeloma screen – again may be included as part of a standard care bundle, but consider in patients with significant proteinuria, raised serum globulin and non-specific symptoms.

- HIV/Hep B/Hep C – all of these may be causative and are certainly important to know a patients status if acutely unwell and no obvious cause is present.

- Creatinine Kinase – rhabdomyolysis is an important cause of AKI to find and treat. The typical patient we imagine is an elderly person with a prolonged lie on the floor following a fall. Remember though, any patient can also develop rhabdomyolysis following crush injuries, myositis and from some poisons/overdoses to name a few.

- ECG – cardiac ischaemia or infarction may be the cause of an AKI or it may show changes relating to electrolyte disturbances that need treating.

- CXR – may demonstrate fluid overload as a complication of AKI or could show a pesky pneumonia as the cause among others.

Management

AKI is a medical emergency and requires urgent attention

Acutely unwell patients need active and involved resuscitation to correct abnormal or unstable physiology

If you are concerned about the patient, escalate to your seniors or nephrology/critical care early

As with any acutely unwell patient, following a structured ABCDE approach is a good place to start with the primary aim of identifying the acutely unwell patient and instigating resuscitative efforts with the aim of correcting abnormal physiology.

Complications of AKI need to be saught and managed (see part 2):

- Hyperkalaemia

- Fluid overload

- Acidosis

- Uraemia

The mainstay of management for AKI is to treat the underlying cause. Your local guidance and protocol will help you with this. For discussion here are some areas that can prove difficult. Anything above the basics will likely need discussion with specialist services.

IV Fluids

One area of management that can cause trouble is the provision of IV fluids. A common practice that sometimes occurs is to prescribe a slow bag of IV crystalloid over 8-12 hours. Certainly, if there is a pre-renal component related to low renal perfusion or circulating volume then IV fluids may well be needed. Similarly, if a patient is not able to maintain their own daily intake of fluids then supplemental fluids may well be necessary. The need for IV fluids should be based upon assessment of the patient’s volume status itself.

If a patient has derranged haemodynamics and signs of shock, they need IV fluid boluses with regular reassessment of the response. If you find you are giving large volumes of IV fluids or the patient is not stabilising or only transiently responds, they need discussion with critical care. These patients need early discussion, even if they don’t need extra support at that moment, they need highlighting early.

Be wary of simply increasing a background IV fluid infusion rate as a way of delivering more fluid to the patient. It is very easy to do, however can lead to a “fluid creep” that can see patients receiving large volumes of fluids which can have a negative impact on their outcomes (8).

Ideally, you should be adjusting fluid according to haemodynamics and urine output. We should be aiming for a urine output >0.5ml/kg/day. A urine output that is not matching this or is falling despite adequate volume replacement may be a sign that the AKI is not resolving and more intense treatment is required. The urine output does not necessarily need monitoring with a urinary catheter though. Patients who are alert, orientated, stable and able to void into a gender appropriate recepticle can have their urine output monitored by these means. Catheters are invasive things that carry their own risks. However, if a patient is unable to void into a recepticle or is acutely unwell, especially if unstable, then a catheter is certainly justified.

Which fluid do you prescribe? “Normal” Saline has received a lot of attention recently for the wrong reasons. The SPLIT trial (9) sought to investigate this amongst intensive care patients, comparing buffered crystalloid (plasmalyte-148) and found no difference between rates of AKI among patient groups. These patients however, were in intensive care units and AKI was diagnosed by the RIFLE criteria which is not what is commonly in use in the UK. A study by Yunos et al (10) has sought to examine the effect of chloride liberal versus restrictive fluids strategies for patients admitted via the Emergency Department in a tertiary centre situated in Melbourne, Australia. They did find reduced rates of AKI Stage 3 amongst patients on the chloride restrictive arm of the study but no difference in mortality or rates of Renal Replacement Therapy (RRT).

Whilst it is obvious there are serious concerns about the safety of 0.9% Sodium Chloride (“normal” saline) (9-11), as yet, there is no definite answer regarding what is better in its stead. Rather than being bogged down by the weight of deciding on Hartmann’s or Saline, choose the fluid that is right for the patient in front of you, remembering that is fluid is not working and the patient is not stabilising or responding they need escalating.

Medication & Nephrotoxins

This category is broad. It encompasses any medication that could have a negative impact upon renal function and some medication that will need doses adjusting for renal function.

The important drugs to consider are ACE-inhibitors, Angiotensin II blockers and NSAIDs. Diuretics will need due attention also. As part of your initial assessment, a drug history should have been taken, or, if already an inpatient, consult the drug chart.

Antibiotics such as gentamicin, teicoplanin and vancomycin (to name but a few) can impact on renal function and will need careful monitoring and consideration of dose adjustment as necessary. Tazobactum/piperacillin (Tazocin) also needs a dose adjustment in severe renal impairment with eGFR <20 and becomes a twice daily dose rather than three times daily.

One point from experience though is when considering stopping nephrotoxic medication, especially for those with concomittant heart failure, is to be weary of abruptly stopping everything. For some patients, the ACE-inhibitor and diuretics may be crucial. Not in all patients though and in most you can stop and reintroduce later once the renal function has improved again. However, for these patients where certain medications are vital, it is worth consulting the relevant speciality for guidance. AKI becomes much more difficult to manage if heart failure becomes rampant. Many other medications will need dose adjustments making and you will need to consider each medication the patient is prescribed in turn.

Contrast media for CT scans is an interesting point. It is included in guidance for AKI as a potential nephrotoxin. However, the most up to date evidence would suggest that intravenous contrast does not carry the same risk that it is often labelled with (12). Arterial contrast for angiograms is different. That being said, you are unlikely to convince radiology of this and may struggle to request scans that require IV contrast without knowledge of renal function. In emergency situations, the time required to provide volume expansion prior to CT scans may not be available to you and the investigation needs to happen immediately, regardless of renal function, becasue the risk of delay far outweighs that of allowing pre-loading with fluids. Similarly, there will be some patients where giving large volumes of fluids to allow for IV contrast could worsen their clinical situation if already fluid overloaded. More junior doctors would not be expected to make these decisions themselves and if you have any doubt then speak with your seniors about the best course of action for the patient in front of you.

Referral

Any patient with a Stage 3 AKI should be referred to nephrology regardless of cause (5, 6).

Any patient with an AKI who is critically unwell should be referred to Critical Care especially if complications are present and not responding to initial medical therapy (5, 6):

- Hyperkalaemia

- Anuria

- Acidosis

- Uraemia

- Fluid overload/pulmonary oedema

Any patient with an obsrtuctive cause shoud be referred urgently to Urology (5, 6)

Your local nephrology service will have agreed referral criteria in place as part of the AKI guidance. The patient to consider referral for include:

- Stage 3 AKI

- AKI of any stage that is not responding adeqautely to treatment

- AKI with no clear cause

- AKI with complications associated with AKI

- Renal transplant patients

- Stage 4 or 5 CKD

- Possible specialist diagnosis (eg myeloma, vasculitis, glomerulonephritis)

Increasingly, patients who have had AKI are followed up follwing discharge. The exact follow up will be determined locally. For some patients, it will be appropriate for the GP to monitor renal function in the community. For some patients, nephrology themselves may wish to follow up. Consult local guidance and your seniors in order to determine how to procede.

Vasculitis & Special Diagnoses

As Aled mentions, diagnosing vasculitis is difficult. The symptomology is often vague, non-specific and variable. Certianly, some places will mandate vasculitis screening as a standard in all Stage 2 and 3 AKIs. If you have no clear cause for AKI then it is worth considering.

Vasculitis is more common in the older patient but can occur at any age. Lethargy may be a prominant feature with loss of apetite and weight. A petechial rash may be present alongside joint pain. There may also be a personal or family history of autoimmune, connective tissue or vasculitic disease processes.

The screening tests to order could include:

- ANA

- ENA

- Complement C3/4

- ANCA serology

- Anti-Double stranded DNA antibodies

- If pulmonary involvement – anti-glomerluar basement membrane antibody

- A high protein on urine dip will require a formal urine protein/creatinine ratio

Remember: 10% of ANCA vasculitis is negative. If there is a strong suspicion of a vasculitis as a cause of AKI, consider referring these patients early to Nephrology as the confirmatory blood tests may take a few days to return and waiting may delay treatment.

In older patients with non-specific symptoms, the diagnosis could as easily be myeloma as vasculitis. Some tests will differ based on local policy, but the testing to consider would include:

- Urine dip – with increased protein loss

- Full blood count – looking for anaemia

- Calcium/bone profile – hypercalcaemia and/or raised Alkaline Phosphatase

- Serum electrophoresis

- Serum free light chains

When the diagnosis of myeloma is suspected or confirmed, input from a Haematologist early on is essential to managing these patients.

In patients with a positive ANCA result or high suspician of an intrinsic renal cause, a tissue biopsy will be required in order to make an accurate diagnosis. However, the need for this will be guided by specialist services and should only be ordered after discussion with them.

Take home points

The diagnosis of Acute Kidney Injury is a medical emergency and should be treated with the seriousness this implies. The management can be simple or complicated but all depends upon the likely cause and condition of the patient. Early referral to critical care or nephrology can make a big difference to the course of the patient’s condition. AKI management is more than simply a slow bag of IV fluids and requires active and involved management with careful consideration of what fluids and medication are prescribed.

Part 2 will cover the complications of AKI and some special situations so stay tuned!!

Speak soon

Gareth

@garEMlyn

GET IN TOUCH! Either through the comments section or email foamdation@gmail.com if there are any comments or corrections or if you want to be involved with future topics.

RATE US on iTunes to help others find the resource more easily!

SHARE US with others you think would benefit or even your training leads to help us distribute the resource further! Twitter: @FOAMdation

References

- Susantitaphong P et al, World incidence of AKI: a meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. Sep; 2013 8(9):1482–1493.

- Press Association, 1,000 hospital patients die each month from avoidable kidney problems. The Guardian, Published 22/04/14, accessed 30/03/18. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/apr/22/avoidable-deaths-acute-kidney-injury

- Challiner R et al, Incidence and consequence of acute kidney injury in unselected emergency admissions to a large acute UK hospital trust. BMC Nephrol. 2014 May 29;15:84

- Silver SA et al, 30-Day Readmissions After an Acute Kidney Injury Hospitalization. Am J Med. 2017 Feb;130(2):163-172

- NICE Clinical Guideline [CG169], Acute kidney injury: prevention, detection and management. Published August 2013

- London AKI Network Manual, version 2.0, 2015. Last accessed 21/04/18 via: http://www.londonaki.net/clinical/guidelines-pathways.html

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney inter., Suppl. 2012; 2: 1–138.

- Payen D et al, A positive fluid balance is associated with a worse outcome in patients with acute renal failure. Crit Care. 2008;12(3):R74. Epub 2008 Jun 4.

3 replies on “Acute Kidney Injury – Part 1”

[…] of AKI. If you missed Part 1 which focussed on some general considerations AKI then check it out here. Or listen to part […]

LikeLike

[…] site contains over 20 podcasts on relevant FY topics including common scenarios such as falls, AKI and prescribing antibiotics, as well as section on practical advice about ‘how to be a junior […]

LikeLike

[…] USS KUB, urine dip and albumin/creatinine ratio (ACR) *please listen to AKI podcast for more info (Part 1/Part 2* and involve the nephrology specialists. THEN, once the cause for renal dysfuction is still […]

LikeLike